"No, no, I never said that the Count had his entire staff executed to cover his tracks. The etching simply suggests—to an imaginative reader—that he might have done so, if he was the kind of person given to doing such things..."

- —Doktor Siegel, satirical etcher[1b]

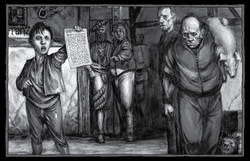

A Newssheet Vendor calls out the top headlines of the day.

The Glorious Revolution of the People (Reformed) is a radical political organisation led by the the Kislevite Prince Aleksandr Kloszowski that seeks to overthrow the feudal autocracy of the Empire and replace it with a more just, democratic government that will engage in large-scale land reform and redistribution of income to end the nation's extremes of social and economic inequality. In its earlier incarnation it was responsible for the outbreak of the Great Fog Riots in Altdorf.

Ten years ago, the great poet and champion of the people, Prince Aleksandr Kloszowski, led a revolution on the streets of Altdorf. But the revolution faltered, the people were slaughtered, and the prince was forced to flee. Ten years later, the prince has returned to the Empire, and he has learnt much in his absence, and from his previous failures. The people will not be saved by one violent action, no more than a single stab of a sword, no matter how deep it cuts the flesh, can win a war.[1a]

Wars are won by attrition, by the slow, grinding establishment of an enemy presence, until the losers can't remember what they were fighting for anymore. Wars are won by controlling the hearts and minds of the whole nation, not just a small army. Wars are won by words, not steel.[1a]

Words are the stock and trade of the Glorious Revolution of the People. The revolutionaries have stopped trying to raise an army and instead have started recruiting a nation. At least, that's the goal. Until recently, not many people bought their broadsheet, the Griffon's Tail, dismissing it as just another scandal-mongering broadsheet or fanciful tabloid. But the Tail is more than just that. It's satirical, it's clever, and it dares to mock the powers that be in a way that's never been done before. The Tail is so exciting its words are appearing on the stage and the street every day, and are read aloud in half the pubs in the city every night. It's an underground journal that's just gone public, and the public are amused. Now, the Tail doesn't need readers, it needs writers—by the wagonload.[1a][1b]

History[]

"And there is forever now a part of me

That lies there in darkness screaming

As bloody sin brought forth bloody tide

'Pon those streets of daemons' dreaming

From out th'Altdorf fog came Altdorf death

A blade in velvet-recluse hidden

T'was always the way in Altdorf life

What other death could we have bidden?"

- —From "The Blood of Innocents," by Prince Kloszowski[1d]

Prince Vladimir Mikael Kloszowski is a real prince. His mother is the Dowager Princess of Inkodeyna, a small stronghold near the capital of the frozen northern land of Kislev. Fearing that her enemies would use her only male heir to oust her from her husband's throne, the princess sent her son away to the Empire to be educated as soon as he could speak their guttural southern tongue of Reikspiel. Kloszowski proved to be a good student, absorbing everything he saw around him. And what he saw made him angry.[1b]

The moment he left his mother's palace he was struck by the difference between the poor and the rich, as the Kislevite muzhiks slaved in the cold just a few feet from what had been his bedroom. The Empire, he was told as he travelled, was a land of opportunity, where power came from earned wealth as much as birth, and no man was slave to another. This, he discovered, was a hollow lie, and the poor slaved and died in just the same way they did in his homeland.[1b]

Bitter and troubled, Kloszowski left his studies and traveled the Empire alone, trying to learn and understand the plight of the people. He wrote poems as he went, sending them back to his old university chums. He was as surprised to hear they had decided to publish them, and even moreso that they were popular. When he came back to Altdorf, he was widely welcomed as a returning hero. His poetry had created a revolution while he had been gone, and he was thrilled to be its champion.[1b]

There were other groups amassing at that time. Ulli von Tasseninck and Professor Brustellin had taught their students about the horrific abuses of the nobility. Another Kislevite, Yevgeny Yefimovich, screamed himself hoarse on the streets each day, and the poor believed his every word. When the pattern murders started, Kloszowski wrote a poem called The Ashes of Shame which implied what they all knew: that the murderer was a noble making sport with the common folk, a symptom of the sickness that entrapped them all. Two days later, Yefimovich printed the poem in a pamphlet that was soon being read in every tavern in the city.[1b][1c]

That night, the revolution began and Altdorf burned. But in the chaos of the fires and the fog and the random violence of the Altdorf mobs, the revolution became nothing but another riot, remembered as the Great Fog Riots. The destruction was rampant, and in the subsequent investigation, it was the revolutionaries who were blamed, especially when Yefimovich was revealed to be a mutant with dark powers. Brustellin was murdered, Tasseninck beheaded, and Kloszowski fled to Tilea, turning his poetry to the more delicate art of seduction as a way to shake off his bitterness and disappointment.[1b][1c]

But he could never stop his revolutionary heart. He returned to his scholarly ways, reading works from the libraries of Tilea and Estalia as he travelled those lands. As he observed the power of the Cult of Myrmidia and read the examples of the wise goddess herself, he saw how great words could unite people and win battles. Although still an atheist, he took the mythical example of Myrmidia as a way in which he could bring true revolution to the people, through educating them. And he knew from his days as a poet the best way to educate people was without them knowing it -- by hiding revolution behind comedy and tragedy.[1c]

He returned to the Empire with a new mission, and a reborn zeal. He would create a free press that published on a weekly basis. Once, his poems had brought a revolution overnight. If that kind of writing entered the culture of the Empire each week, every week, soon some people would not be able to think otherwise. And when enough people thought that, it wouldn't be a revolution anymore, because it would be the status quo.[1c]

There were others who quickly joined his cause. Although not in as many numbers, he was once again welcomed as a hero back to Altdorf. His poem about the slaughter during the Great Fog Riots, The Blood of Innocents, had become another underground classic in his absence, and a clutch of hard-core fans and adherents remained. From them, he drew a group of writers, scribes, and etchers. With the fortune he had made in Estalia, he recruited a Dwarfen printer and rented a tiny basement room near the docks. A month later, the first issue of the Griffon's Tail was printed.[1c]

The GRP at Present[]

|

Attention, Empire Citizens!

This article or this section of the article contains information regarding the Storm of Chaos campaign and its aftermath, which is now considered a non-canon, alternate timeline.

|

For the first eight months the Griffon's Tail gradually gained an audience on the streets of Altdorf, although not a very large or impressive one. Then something amazing happened. On a whim, Kloszowski penned a short play for an issue, in which Grand Marshall Kurt Helborg and Emperor Karl Franz discussed how useful it was that the young warrior Valten had died during the Siege of Middenheim during the Storm of Chaos campaign. A week later, the Angry Goblin Theatre Company performed the sketch on the stage in the run-down Arena Inn.[1c]

The next night, the inn was packed, and a week later, the Angry Goblin Theatre Company was performing it at the Sinner's Stage. A week after that, half the theatres in the city were running it between acts, and clamouring for the Tail to run new scripts. Older issues resurfaced, and Kloszowski's humorous poems and haranguing editorials were recited as well. In a month, Kloszowski -- still writing under the pseudonym "The Tail Puller" -- had become the toast of the town. He had always wanted to be a great dramatic poet, but had found fame as the satirist of his age.[1c]

By the time the nobility caught on, it was already too late. Noblemen and women were already going out (in poor disguises) to catch these scandalous plays or purchase the pamphlets. When the militia raided the Hanged Man Theatre and arrested the entire cast, it only increased the popularity of the works.[1c][1d]

Whilst a dozen actors rot in Mundsen Keep, half a hundred now clamor for the chance to also suffer such a wonderfully romantic fate. Young sons and daughters are ordered never to sully their minds with such things, but their parents sneak out "only to see what all the fuss is about." Priests and zealots decry the terrible sins of these heretical works that dare to mock the gods themselves, whilst pastors hand copies around their choirs for a good laugh. The dam has burst, and only the extermination of the Tail's writers and organisers can stop the flow.[1d]

Desperate to meet the rising demand but keen to protect the safety of his staff and himself, Kloszowski did not expand his tiny operation. Rather, he gave leave for others to set up their own basement printing houses. There are now three Tails in Altdorf: The Griffon's Tail, the original; Tail of the University, working the north side of the city; and Tail of the Gods, serving the area near the Holy Temple of Sigmar to the west. Each edition has its own staff of writers, etchers, and printers, its own content, and its own delivery routes, and some people love to collect all three and compare them. In a few pubs, discussions and minor brawls have broken out over which edition is the best. Meanwhile, Kloszowski has also sent his students out to Middenheim, Talabheim, and Nuln to repeat what he'd done in Altdorf.[1d]

Kloszowski initially wrote letters to keep in contact with the editors of each edition, but eventually instead published another, private, journal titled The Rising Whisper. This helps keep the groups in contact with each other and, more importantly, keeps them inspired. Each issue of the Whisper is filled with Kloszowski's inflammatory diatribes, encouraging editors and staff to keep up the fight and not lose hope. Truth be told, this often falls on deaf ears, for as many are drawn to the Tail for fame and fortune as they are due to political zeal. But it is dangerous, and increasingly so, to work for the Tail, so Kloszowski's urgings for security are always well-heeded.[1d]

So far, the nobles and the Altdorf Watch have been stymied in part by the fact that there are simply no existing laws against publishing. Individual works and books can be condemned as illegal or heretical but the Tail changes its content every week. In times past, there might have been only fifty copies of a book—heavy, vellum-bound things that few could hide -- so burning them all was no great problem. But a thousand single pieces of paper cannot be controlled that way, so no laws exist to do so. Plays too can be banned, players charged, and playwrights executed, but the writers of the Tail remain anonymous and the directors can honestly say they have no idea who writes them.[1d]

Watchmen can typically only arrest actors and sellers for disturbing the peace or causing civil unrest, which results in a fine or a night in the cells. The stars of the Hanged Man got a year for sedition and treachery but as the popularity of the works grows, lawyers are finding it harder to make such charges stick. It is difficult to argue that lampooning the nobility is illegal when half the audience are nobles. Destruction is another solution: play sets can be broken up, stalls smashed, ink bottles and papers seized, and paper-sellers evicted, but the writers themselves manage to continue. That said, not all watchmen need laws, and more than one patrol has been paid handsomely to beat Tail-sellers until their skulls caved in. Other nobles have payed assassins or street gangs to take revenge for the insults printed about them.[1d]

Recently, the Grand Theogonist of the Cult of Sigmar declared the Tail, "a clear and present threat against the sanctity and security of the Holy Cult of Sigmar." This stops short of labeling the journal heretical, but it has allowed zealots and knights to step in where the watch or militias have failed. Of course, many such types had already done so off their own bat, and community temples and splinter groups continue to raise angry protest about the mockery of their sacred beliefs. When the Altdorf Watch seized a large stack of paper and ink but let the student carrying them go without a charge, Sigmarite justice moved swiftly to "correct" the mistake right there on the streets. A riot was prevented, and the student put in the cells for his own safety -- but he was murdered the next day upon his release. The Altdorf Watch simply failed to investigate. One less trouble-making writer is one less day's work for them.[1d][1e]

Which is the real danger for the Tail: They have so far escaped the condemnation of the law of the Empire, but they also get no protection from it whatsoever. They have no recourse when their members are beaten or murdered or their stock destroyed, except to find a new hiding place or a better disguise. What's more, although the paper is growing as a whole, the individual editions are small and fragile affairs. If two or three sellers get beaten in a week, it may take a month for a paper to find a replacement brave enough to walk the streets again. Which raises the other issue hanging over the head of the Tail: money.[1e]

Despite the popularity of the paper, selling it can still be a struggle, and distributed with the Rising Whisper are purses of funds from Kloszowski's personal fortune. Kloszowski has realised this can't last forever, though. He has also realised that capitalism is the key to the success of the Tail on one hand, and to the general freedom of the oppressed classes on the other. Through the fair and even hand of the market, that which the people decide is of the most value shall be given the greatest wealth -- a truly perfect society.[1e]

So Kloszowski stresses in the Whisper that the papers must strive to become self-supporting, and the issue of price is constantly debated. As they can now reach middle class people and the nobility, they can charge sufficiently to meet their costs, but to do so will exclude their poorer readers, something every proletariat-championing editor is loath to do. In Altdorf, the price is listed as 10p a copy, but it is left up to individual editors (and indeed, sellers) how much is actually charged (and how much is skimmed off the top by the seller).[1e]

Purpose[]

The mission of the GRP is to subvert the hearts and minds of the people of the Empire to their point of view. They want to teach the people that the concepts of monarchy and nobility are inherently flawed and evil, and lead only to oppression. They want to encourage people to see that the nobles are nothing but Humans, and foolish and cruel Humans to boot, and their position as rulers is an historical accident, not mandated by the gods. That kings and princes only acquire power because the people let them have that power -- and those same people can take that power away.[1b]

To the average Imperial peasant, this is a very hard sell, but the Glorious Revolution of the People is prepared to start small.[1b]

First of all, they are focusing on the growing (and increasingly more educated) middle classes of the great Imperial cities -- Altdorf, Nuln, Middenheim, and Talabheim. And before they get to the idea of tearing down the nobility, they have begun with the simple idea of mocking and undermining it. And it is this -- the focus on parody over preaching -- that has caught the public eye. It also helps that they print a variety of satirical pictures and primitive cartoons, and that their plays and scripts are now appearing on the stages. Those who cannot afford the plays can see the skits played in the streets, or hear them read aloud by a literate friend over drinks at the pub. This has enabled even the commonest of men to enjoy the comedy of the Griffon's Tail, and they enjoy it very much. The revolution has begun, and it is spreading like wildfire.[1b]

In fact, the Tail has become so successful so quickly it can barely keep up with the demand. What it needs right now is people: writers, artists, reporters, jesters, printers, merchants, runners, messengers, delivery boys, demagogues, bodyguards, and thieves, to help keep up with the demand for issues all across the Empire. So desperate are they for staff they no longer care if all their members are as ardently political as the founders -- and at the same time, the issues are now selling enough copies to attract talented staff who will adopt any political bent required of them in order to gain fame or fortune.[1b]

But to write for the Tail is to have a price on your head and a dramatically lowered life expectancy, as the paper is becoming a major threat to the status quo. The nobility, the cults, the military, and all the powers that be, have all been insulted by the Tail.[1b]

Whether seeking personal revenge or because they realise the danger the Tail represents, those powers that be have declared war. This has driven demand even higher, but has also made getting the Tail out each week harder and harder. Words are the steel of revolution, but they also need real steel -- and those who can wield it -- to get those words to their audience.[1b]

The revolution needs people willing to get their hands dirty with more than ink. In secret, Kloszowski's war has begun.[1b]

Structure[]

Without deliberately planning to, Kloszowski developed the Tail into a cunning cell-structure. In each publication house, only the editor is in contact with Kloszowski, and only then through the Rising Whisper. Some have not even met Kloszowski at all, and few know his real name. This is vital for maintaining security, although there are still vulnerabilities. Kloszowski employs horse messengers to send the Rising Whisper to his editors across the land and although he uses people he trusts and pays them fairly well, any of them could lead authorities straight back to the Tail's editor-in-chief.[1e]

And at this point, the organisation definitely could not survive without its founder: the loss of his inspirational words would be crippling to morale, and the loss of his financial support would leave the tiny printing presses stranded and vulnerable. Not to mention that Kloszowski's writings appear in at least every second issue and every edition would be hard-pressed to publish without him constantly filling their pages with his brilliant satire, and would find it harder to attract an audience as well.[1e]

Beneath Kloszowski are the editors. As long as they agree with him on the purpose of the journal and hire talented writers, Kloszowski leaves the running of their papers up to them. There are no written rules or practices for administration or operation. As such, editorial and organisational styles vary wildly across the different editions. Some editors are fair employers, others are egomaniacal tyrants, and still others treat their writers and staff as equal parts of a creative circle. Some love to whip up scandal, others prefer to focus on content over reaction; some are parsimonious number-crunchers, others leave aside all concerns but the creative; some delegate such responsibilities as they cannot or will not do themselves, others are micromanagers who work themselves into a flurry over every stage of the operation.[1e][1f]

How well the journal reads and how successfully it operates depends on both the editor and the staff that surrounds them. Due to the high risks of the occupation and the high-pressure nature of the work, the staff can change quite frequently -- which produces another security vulnerability. Leaving ex-staff are sworn to the same secrecy as newly joining staff, but there are no checks upon their loyalty. However, not only do staff change regularly but so do locations and operations -- there may be little an ex-staffer could tell. More than one edition has been compromised, however, after a writer whose stories were rejected tipped off the Altdorf Watch, or an ingraver decided he needed more than a weekly pittance for his work.[1f]

When an editor leaves, they either selects their successor or someone just steps into the role. The successors are usually whomever has the most time, talent, and passion for the project. Since the editor receives no more fame than their writers (often less) and has to fill each issue and run the whole organisation, it is a job only taken by gluttons for punishment, and is a position rarely challenged. Which is not to say that some editions are not riven with interpersonal politics and petty jealousies -- sometimes it is the very smallest of honours that brings out the fieriest ambitions.[1f]

Getting a writing job with the Griffon's Tail involves impressing the editor with your skills. Given that Kloszowski is a genius and his early associates are practiced professionals, there is a high standard to reach, and competition for space in the broadsheet is steep and furious. However, the Tail has a desperate need for staff to do almost everything else. This includes the most basic of tasks, such as standing look out on a street corner or answering the door above the printing office in such a way as to not arouse suspicion. They need riders to help their issues get across the city and into the villages beyond it. They need bodyguards to keep their deliveries safe, and smugglers to help their supplies arrive, merchants to help them get good deals, rogues to make sure their secrets stay safe, barkers to sell their wares on the corner, and stooges at the tavern to encourage folk to go and buy them.[1f]

All who join are sworn to secrecy, but few of the editors know very much about criminal organisation. They may have run the odd "underground" journal at university but again, as the Tail has grown, it has become something on an all-together-different scale, beyond even Kloszowski's ability to organise and keep secret. Many editors have considered turning to organised crime for help and tutelage in this manner. Some editors already have.[1f]

Goals and Motives[]

The overarching goal of the Glorious Revolution of the People (Reformed) is the complete destruction of the noble order and all its lackeys. After this, a new rule must be formed in which the people are only governed by those deemed by the people as most fit to govern, although the details of how this would work remain as yet unspecified. This reform does not include destruction of the Cult of Sigmar, but in rebuilding a truly democratic people's republic, the Empire's state church would no longer be permitted to play a role in politics, so its power must also be heavily curtailed. The Cult of Sigmar's crime is not in preaching its faith but in supporting the blood-sucking nobles and standing against the glorious movement to bring them to their knees.[1f]

As yet, the Glorious Revolution has no fixed timeline for these goals.[1f]

Their more short-term goal is the spreading of the idea of revolution through the propagation of The Griffon's Tail. The Glorious Revolution does not particularly mind in what form the destruction of the nobles comes: it may be in a sudden hammer-blow, but it may also be in the slow weathering of their hold over people's minds and beliefs. The greatest threat to the Glorious Revolution is not the guns, faith, and steel of the noble classes and their lapdog military, but the belief of the common man that they deserve to be ruled, that nobles are inherently better than they, that their feudal, hierarchical life is the natural order of things. Kloszowski and his revolutionaries believe that the more they can educate and inspire, the closer their revolution comes.[1f]

So far, they have focused on satire and mockery, but each edition of the Tail includes some items of direct polemic or rabble rousing. A lot of people skip those parts, but not everybody.[1f]

On an individual level, the goal of each edition of the Tail is to stay in operation and try and make money. Neither of these are very easy tasks, for countless reasons. Some editors are focused so much on these goals that the revolution has become something of a secondary concern. Other editors and writers have other goals, which interfere with the pursuit of revolution or profit: they want to become famous, or at least recognised or connected.[1f]

A playwright seeking a contract with one of the major theatres or a poet seeking a patron could get noticed in the Tail. Others just enjoy the notoriety of it all, finding it a jolly good lark. Still others use the broadsheet as a way of settling old grudges: For example, should a low-ranked noble be prevented from marrying his better's daughter, he can savage her father in anonymity on the pages of the Tail.[1f]

In short, the goals of the Tail are very specific, but the reasons that people join its cause are as varied as the people themselves.[1f]

Symbols and Signs[]

The symbol of the Glorious Revolution of the People (Reformed) is a stylized eye, with a flame around and above it. The eye comes from an old symbol of Shallya, the goddess of mercy and healing, which was an eye crying a single tear. In this symbol, the teardrop becomes a flame, symbolising that from the suffering poor will come the purifying fire of the revolution. The eye in the flame also reflects illumination, the shining truth of the revolution and the opening of people's eyes to the oppression upon them. Full members of the Glorious Revolution have this symbol tattooed on their breast and Kloszowski puts it on the front of every issue of the Rising Whisper.[1g]

The original symbol of the Tail was a comically-styled backside of a Griffon, its tail flicking above a pile of manure. Upon the Griffon rode a pompous and gaudy noble figure, only slightly reminiscent of the emperor. This picture also featured two peasants with shovels, forced to deal with the muck left by the passing noble. This proved too busy for other etchers to copy and the printers could not make the symbol reliably into an inking key. It was instead simplified to a winding, spotted tail.[1g]

When members wish to identify each other or use code words, they typically take lines from The Ashes of Shame or The Blood of Innocents or another of Kloszowski's popular works. The greeter gives a line and the arrival must provide the subsequent one. Thus anyone who knows the works well could break their security, but so far it hasn't happened -- that they know of.[1g]

When writing their articles, all writers and editors use pseudonyms or titles. Kloszowski generally writes as "The Tail Puller," but also sometimes uses "The Old Poet" and "Ulrike's Son" (Ulrike was a champion of the revolution in the Great Fog Riots ten years ago). Letters and codes are typically also signed with these pseudonyms, increasing security as many will only know each other by these names. Some authors have only met their editors briefly, dropping off work anonymously with only their monicker or symbol at the bottom. A writer known only as "The Dark Lady" has never revealed her face to anyone, appearing only once at the office in Nuln and then with her face covered in a scarf and hood.[1g]

Membership[]

Apart from the delivery boys and bodyguards, most of the Tail's staff must be able to read. Even the street-corner barkers need to know what's in each issue, and messengers need to know the codes and changing addresses. Inevitably, therefore, most staff-members come from the growing "middle-classes" of the Empire: those who were brought up with sufficient wealth to be able to learn to read, and sufficient indolence to pursue more than just a living. Surprisingly, many of the staff are also nobles themselves. Whether they are sympathetic to the plight of the lower classes or simply enjoying the lark depends on the individual, and whomever they are trying to impress at the time.[1g]

The rest of the staff tend to be the children of merchants, craftsmen, and guild masters, or gifted students from the universities. Most of them have some kind of scholarly background, be it as a student or scribe, or having just acquired broad knowledge while learning their trade. For a student leaving university (and thus giving up on being a scholar), there are very few opportunities beyond returning to their father's business. Working for the Tail (or any other paper) is a great way for such types to postpone the inevitable. Apprentice wizards who have failed their exams also find their way into such places as a way of filling in time before they figure out what to do next, and the same goes for initiates of the cults who have lost their faith or failed to meet the standards of the cloth. Adopting a cause has always been a great solution for the lost.[1g]

However, there are more than just scholars working for the Tail. Just as any person with a cause they feel deeply enough will gravitate towards the soapboxes in the squares, so too do the passionate and/or insane gravitate towards the offices of the Tail, and they come in all kinds of guises. Passion finds its seeds in strife, and strife affects the young and the old equally, the rich and the poor, the Human and Dwarf, the Elf and the Halfling, the educated and the unlearned, the brilliant and the foolish. The Tail tries to steer away from the people ranting about the Daemons controlling Bogenhafen and the like, but they can rarely afford to be very picky. They do however ask for people to focus on the plight of the underclasses and the oppression by the nobles. A conspiracy theory about, or parody of, wizards or Elves is unlikely to get published.[1g][1h]

The Tail is definitely biased towards Human concerns, partly because almost all of its members are Humans and partly because almost all nobles in the Empire are Humans. Kloszowski and his collaborators recognise that often nobles create scapegoats of the non-Human populations of Imperial cities, but this is just another example of the abuse of power rather than a terrible concern. This has displeased more than a few oppressed Dwarfs and Halflings (and has come to the notice of the Quinsberry Lodge) and will no doubt change as more of these folk join the writing staff.[1h]

This is the general approach of the Tail: those who want the content changed should write it themselves. As Kloszowski puts it, "we don't take complaints, we take submissions." Not only does this generally get rid of complainers, it very occasionally does lead to new members.[1h]

The criminal classes make up the final -- and arguably most important -- type of revolutionary. Although Kloszowski knows a fair amount about raising an army from the streets, his skills in running a long-term criminal organisation are limited. Employing people who do know these things is useful, as is employing those who have previous experience with the kind of things the journal requires. A lookout is a lookout, regardless of whether they are protecting smugglers or authors. Bauds make excellent barkers, as they know exactly how to capture the eye of any passing gent. Street gangmembers tend to know very well how to put issues of the paper on the streets at night without running into the Altdorf Watch. The pay tends to be much worse, but as an extra source of income (and one with less chance of having your legs cut off with a rusty bonesaw), it is attractive to many.[1h]

Recruitment[]

Recruitment into the Tail's staff is extremely poor. Few editions can afford to pay many of their workers more than a pittance; some cannot even afford that. Indeed, those who work the hardest -- the actual writers and editors -- are often paid the least, as all funds are needed to pay the less fanatical members doing the more dangerous jobs. Those who write for the Tail will do it out of passion, but lookouts, runners, message-carriers, suppliers, and toughs all require monetary compensation. Those who come to the Tail looking for a bit of fun or a bit of money leave quickly. Indeed, many who come with passion leave just as quickly when they realise they cannot make any kind of living from the work. Only the true believers or the independently wealthy remain working for the Tail for any length of time.[1h]

It is from these true believers that the Glorious Revolution itself recruits. Those who prove their passion by continuing to write, edit, or run the Tail will eventually be introduced to Kloszowski if they weren't chosen by him originally. He will tell them they have earned a place in the inner circle, and, if they are still unaware, informed officially of the goals of the journal and the organisation of the Glorious Revolution. They are also expected to get their tattoo (see Symbols and Signs above) after this. The difficulty of working for the Tail thus provides a natural filter, ensuring that only those who really believe join the Glorious Revolution.[1h]

Recently, the Tail has tried to appeal to wandering adventurers, seeing this as a fertile recruiting ground. Adventurers tend to do jobs for very little money and unlike local criminals, don't have a syndicate to send thugs around if there is a problem with payment. Adventurers can easily be inspired to do such work for less with tales of how they are helping defend the poor and making the world a better place. They also make excellent scapegoats and diversions, taking the heat away from the actual work of publishing. Finally, they also have a knack for falling into incredible adventures and dark conspiracies, both of which provide excellent fodder for the Tail's writers. More than one Tail writer gets his scandalous stories about the nobility from his discussions with the adventurers originally hired to cover up those very scandals.[1h]

Member Benefits and Responsibilities[]

Recruitment into the Tail is poor because members get few benefits and have a vast amount of responsibilities, plus exposure to great risks as well. Staff are mostly volunteers or effectively so; as yet, only a few can live on the meagre returns the Tail makes from its sales. Like all volunteer associations, the volunteers define their own level of involvement, and the editors give preference to those who do the most work (even if their work is less artful than those of other, less industrious types). Any writer wishing to stay in his editor's good graces (or become an editor himself) needs to produce a completed essay, script, or satirical comment once a week. The higher the quality of work or the more incisive, the more likely it will be printed.[1h]

Non-writers are expected to fulfill their duties sufficiently, although, "sufficiently" is a word whose definition many editors have to revise on a constant basis. There is no gain, for example, in firing a lazy printer if there is thence nobody around who can work the machine. Likewise, a messenger who drinks at every tavern between Altdorf and Middenheim must just be accepted because it is too dangerous and time-consuming to find a replacement.[1h]

Not only is the Tail always short-staffed, but their staff are simply the best they could find at the time. Editors love to see itinerant adventurers with nothing to do, because, sadly, even these mendicants are typically an improvement on their usual staff.[1h]

Those who work for the Tail in a regular fashion can expect a salary of zero to nine shillings a week -- about the same as a country peasant makes, or a bit less than does a common Altdorf labourer. Editors make about double that, assuming that they do not also have to purchase new ink or new printing press parts that week. Apart from editors, most Tail staffers have another source of income or livelihood, whether that is a job, a wealthy background, or some criminal enterprise.[1h][1i]

The Tail offers no other benefits. It can often not even protect its own members. A fleeing seller, for example, with the Altdorf Watch close on his heels, will just as often find himself turned away if he runs to any of his writing colleagues or a printing house for assistance, because supporting him would only threaten the rest of the group. Almost every edition has watched one of their staff be hauled away (or even burnt at the stake), unable to do anything. The survivors tell themselves that the sacrifice of their brave colleague was not in vain, and that the fallen would want nothing more than for the Tail to persevere. Those who survive capture and return to the streets are less likely to see things that way.[1i]

Secrets of the GRP[]

"To your friends and neighbours, you seem to live the life of an ordinary silk merchant and tailor. But at night it seems you go to certain meetings under the Pendersen Brewery, returning in the early hours with your fingers stained with ink. One of these lives has a future that doesn't involve a hot poker to the eyeballs."

- —Benedikt Krieger, Imperial Spy[1i]

Like all revolutionaries, those in the Glorious Revolution of the People (Reformed) live a terribly dangerous existence. On the one hand, they must keep their operations desperately secret, but on the other, they depend entirely on their public face. They seek to expose the truth, yet secrets are their stock in trade. They seek to give power to all the people, yet can trust very few of them. The Glorious Revolution's increasing popularity is its greatest weapon and its greatest threat. And despite pulling towards its singular, unified goal, it is but a collection of individuals, each pulling in their own direction. The Glorious Revolution and the Griffon's Tail exist constantly on the knife-edge, always one step away from doing real good, and one step away from self-destruction; an inch away from starting a new kind of war, and an inch away from being wiped out by their enemies.[1i]

Although they are passionate in their belief that one day the revolution will bring about real change, few of its members are foolish enough to believe this will come soon, or easily. Which is to say everyone is aware how weak and vulnerable the organisation is to attacks from without, and how divided and limited it is within. What most do not know (or try desperately to make themselves forget) is just how compromised they already are, and, despite the sudden success of the Griffon's Tail, how far they truly are from achieving their goals. While mocking the nobility is the new fad sweeping the nation, true revolution lags far behind, whereas death or arrest or simply running out of money are never more than a heartbeat away.[1i]

Each editor deals with their own doubts in their own way, but perhaps the best-kept secret is that even the great Kloszowski has his own doubts and those are large indeed. With each passing year Kloszowski grows more and more tired of waiting for the revolution, and more and more enamoured of himself. Revolutions are for young men, whereas being a hero of the people has compensations that grow sweeter with age. When he isn't writing, Kloszowski is using his reputation to bed the latest wide-eyed young adherent who swooned when she read his poetry. His willingness to brag about himself for the purposes of seduction could easily lead to the destruction of the Glorious Revolution. It offers little danger to his own person, however, because Kloszowski is a survivor first and a revolutionary second.[1i]

He's also spent enough time in prison to decide he is never going back, and he will sell out every editor he knows to ensure that doesn't happen. After all, he thinks, while he lives free the movement will go on, so preserving his freedom is the most important thing of all. Naturally, Kloszowski keeps this fact very hidden -- even from himself.[1i]

Unknown to everyone, including Kloszowski, is how compromised the Tail has become. The very recent parody of Grand Theogonists Esmer and Volkmar as naughty children in Kloszowski's Cries from the Nursery was so popular both on the stage and in print that it is now being parroted in alehouses and markets across the city every single day. This caused the Cult of Sigmar to declare the Tail a clear and present threat to the safety of the Empire. They also convinced many on the Council of State to agree with them, and the spymasters of both the church and state have now put their sizeable resources to work.[1i]

All three of Altdorf's editions of the Griffon's Tail now have spies in their midst (either willing or coerced), and the religious fanatics swelling in opposition to the Tail find themselves very well-funded. Kloszowski himself is currently sleeping with one of the Empire's top spies. She is looking for a way to discredit the man because currently, his reputation is so strong that his death will only inflame his supporters.[1i]

Likewise, the Imperial authorities have not yet closed the net around the Glorious Revolution because they want to do it in such a way as to catch all the vermin at once, and leave no traces of how it was done, so no new groups can follow in its wake. If they can destroy the Glorious Revolution from within, so much the better.[1i]

The other thing protecting the Glorious Revolution is that the spy sleeping with Kloszowski is in fact a member of the Lahmian Sisterhood, a group of female Vampires who secretly control much of the politics of the Empire. The Lahmians are curious as to whether the Glorious Revolution can help their needs, if only by distracting the authorities, so are keeping the society alive for the moment.[1j]

Allies and Enemies[]

Although it cannot trust others, the Gloriuous Revolution of the People has many allies. Many groups find themselves agreeing with the Tail's attacks on the powerful and the status quo, and as the Tail grows more successful, more and more groups are willing to share in that success. Of course, few if any of them would take any risks for their newfound friends.[1j]

The most fervent supporters of the Glorious Revolution are other revolutionary groups. These include the exiles from the Kislev Underground, who spread their ideas of peasant freedom far from their homeland; the unionists from the Artisan's Guild who preach about the rights of the workers; and the Popular League Against Nobility and Taxation, a group of merchants who are annoyed that they will never rule the cities in which they own so much property and wealth. All of these groups disagree with the exact method of revolution, but they can be counted on to unite in any decisive actions and share in any great success.[1j]

Despite the efforts of the authorities of the Empire and the universities, professors and students alike continue to propagate revolutionary and counter-cultural ideas. Many of these students are either working for the Tail already or actively looking to join. Others are in societies with similar aims, or working on their own articles or pamphlets, and these societies also overlap with similar societies run on the streets. Activism is manifold in Altdorf and the other big Imperial cities, and it is not uncommon for a market square now to contain half a dozen pamphleteers, each working for their own particular crusading society with its own unique noble goal. Of course, competition breeds rivalry, and these other societies are enemies of the Tail as well as allies, and on occasion a particularly competitive selling session can end in a punch-up.[1j]

The publishers and staff of the other broadsheets have a similar relationship to the Tail and its staff. Jealousy springs eternal and while they admire the Tail's success, the staff of the Altdorf Spieler and the The Truth and the like would really prefer those sales went to them. In the face of overwhelming odds, like an approaching gang of "concerned citizens" out to drive away the trouble-making broadsheet sellers, it would likely be all journalists together. In safer times, however, Tail sellers may whip off for a call of nature and come back to find their issues have been "accidentally" thrown in the River Reik. Should the stores only contain one last shipment of ink, no editor of any paper is beyond hiring extra shopping muscle to make sure their's is the paper that remains in print.[1j][1k]

Other allies of the Glorious Revolution are more dangerous. To keep itself in operation and with sufficient supplies, the Griffon's Tail has made several deals with organised criminals. On the Docklands, they have turned to the gang known as Fish (Gang)|the Fish]], whom they pay handsomely for protection of their staff and to connect them with certain other criminals. Through the black marketeer Mother Mandelbaum they are able to get access to paper and ink supplies that aren't recorded on any ledgers. These new friends however now have a hold over the Tail and are the kind who will soon enough ask for favours in return. The Tail's staffers are loath to do this.[1k]

Partly because most of them are smart enough to realise that crime lords are just another kind of noble, and partly because it only increases their likelihood of being targeted by the Altdorf Watch, but mostly because they don't want to be thrown in the Reik with heavy weights on their feet, which seems to be the fate of far too many of the Fish's "friends."[1k]

So although the Glorious Revolution of the People counts among its enemies the nobility, the Cult of Sigmar, and the military of the Empire, it is all too often its closest allies that give editors the most trouble sleeping at night.[1k]